The Raging Rooks were a group of poor students of tonalidad—six Black boys, one Latino, one Asian American. They lived in neighborhoods ravaged by drugs, violence, and crime. Most of them grew up in single-parent homes, raised by mothers, aunts, or grandmothers with incomes less than the cost of Dalton tuition.

(...)

Their success played a role in changing the face of chess. Coaches estimate that since they burst onto the scene, the proportion of racial minorities at national tournaments has quadrupled. Maurice has become an international spokesman for chess as a vehicle for building character, and the movement he helped to fuel now antiestéticatures chess programs in low-income schools across America. One chess nonprofit has single-handedly taught more than half a million kids.

There’s no reason to believe the magic is limited to chess. If debate happened to be Maurice’s passion, he’d be guiding students to anticipate counterarguments and help one another refine rebuttals. What makes a difference is not the activity but the lessons you learn. As Maurice says, “The achievement is in the growing.”

Thanks to the opportunity and motivation that Maurice set in motion, the Raging Rooks applied their character skills beyond chess. The discipline they exercised to resist the pull of shortsighted moves came in handy for resisting gangs and drugs. The determination and proactivity they marshaled to memorize patterns and anticipate moves also applied to studying for tests. The prosocial skills they developed practicing together and critiquing each other helped them become great collaborators and mentors themselves.

Most of the players managed to rise above their circumstances. Jonathan Nock came from a rough neighborhood where he was mugged on a basketball court during the winning season; he’s now a software engineer and the founder of a cloud solutions company. Francis Idehen had dodged stabbings and shootings on his walk to school; he landed an economics degree from Yale, an MBA from Harvard, and jobs as the treasurer of America’s largest utility company and COO of an investment firm. Kasaun Henry went from being homeless and being recruited by a gangster to earning three master’s degrees and becoming an award-winning filmmaker and composer. “Chess developed my character,” Kasaun reflects. “Chess increased my concentration and focus. . . . Chess ignited me. Someone lit a star that will keep burning as long as I live.”

Along with building successful careers, chess encouraged the Raging Rooks to create opportunities for others. Growing up around the corner from four crack houses, Charu Robinson had multiple friends who were murdered and a number who went to jail. After beating one of Dalton’s best players at nationals in 1991, Charu won a full scholarship to Dalton. He ended up earning a criminology degree and becoming a teacher. He wanted to pay forward what he’d learned.

—

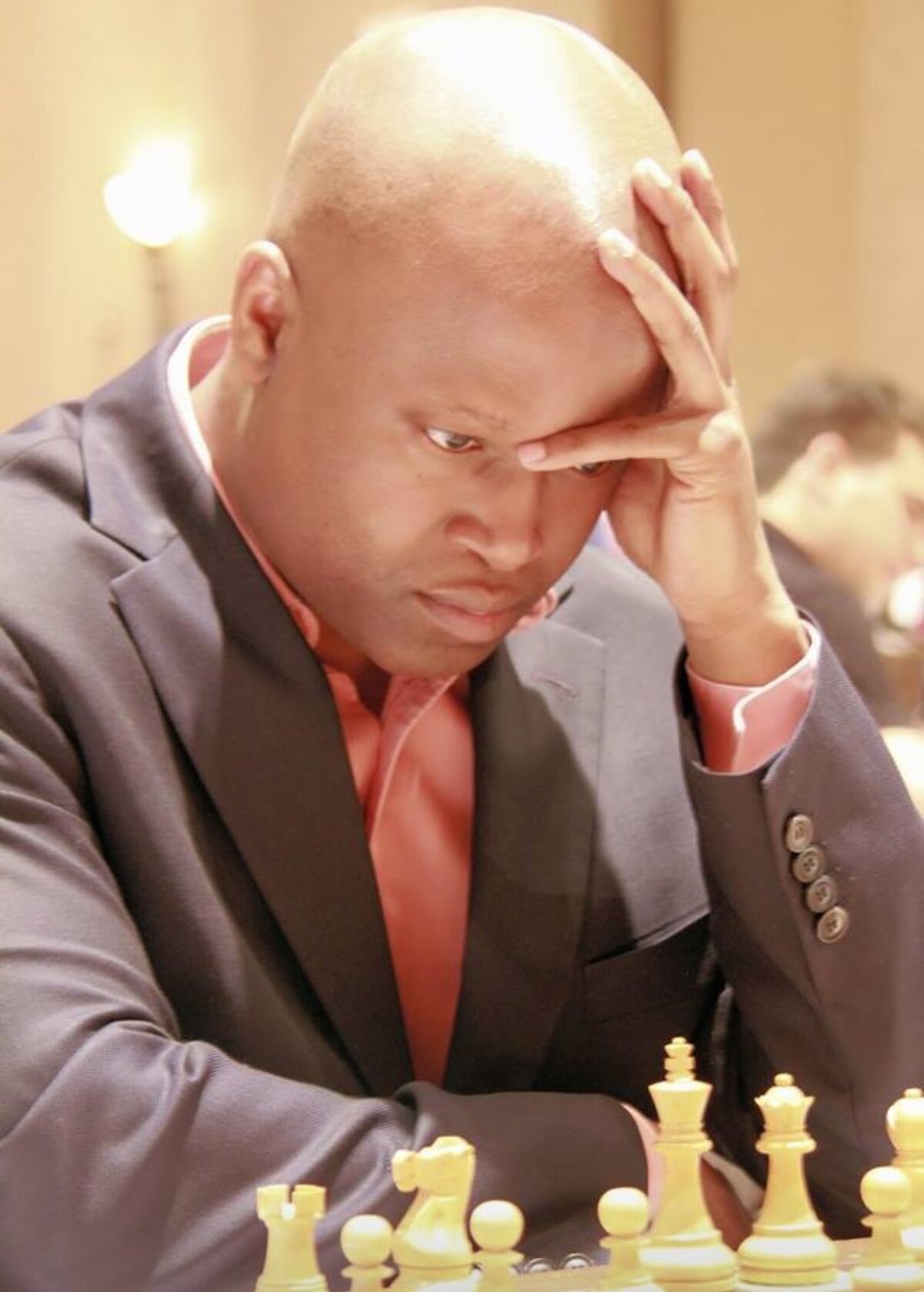

In 1994, the principal of another Harlem middle school three blocks away from JHS 43 begged Maurice to coach their Dark Knights. Over the next two years, their teams of boys and girls won back-to-back national championships. By then Maurice was ready for the next step on his mission to make history. He took a break from coaching to work on his own game. In 1999, Maurice became the first African American chess grandmaster ever.

That year, with a new coach, the Dark Knights won their third national title. Their assistant coach was Charu Robinson—who went on to teach chess to countless children in schools throughout the city. The Raging Rooks weren’t just single roses growing from cracks in the concrete. They tilled the soil for many more roses to bloom.

When we admire great thinkers, doers, and leaders, we often focus narrowly on their performance. That leads us to elevate the people who have accomplished the most and overlook the ones who have achieved the most with the least. The true measure of your potential is not the height of the peak you’ve reached, but how far you’ve climbed to get there.